Hong Kong – Un exemple extrême de développement parasitaire

Otto Kölbl

Hong Kong is generally presented as an example of highly successful economic development and as a possible model for other countries in Asia and across the world. A closer look at the history and development of the island shows that its economic performance is very far from exceptional. Most of its growth was achieved not by the efforts of the Hongkongers, but through parasitic exploitation of neighboring mainland China.

Hong Kong by night, photo David Iliff, license CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Hong Kong's development is based to a large extent on its controlling position over one of the best deep water ports in East Asia. This situation gave Hong Kong a monopoly over the international trade of all the goods produced in the Pearl River Delta. In return, since Hong Kong did not contribute to the budget of the Chinese central government or of Guangdong province, the port city did not assume any responsibility for the development of mainland China. Hong Kong was also one of the main hubs for the opium trade; the development of the city was therefore directly based on exploiting the suffering of the Chinese people and the destruction of the Chinese society on the mainland. The fact that recently, Hong Kong has become one of the main tax havens in the world does not really plead in the city's favor.

The entrance to the port of Hong Kong, ca. 1880. Photo Lai Afong.

This article might seem quite harsh in its tone, but there is a good reason for this: in recent years, I was deeply shocked by the condescending and contemptuous attitude many Hongkongers have shown towards mainlanders. Comparing the mainlanders with "locusts" which invade Hong Kong is totally unacceptable. If the residents of Hong Kong had worked very hard these last decades to develop the island whilst the mainlanders led an idle life and want to benefit now from Hong Kong's prosperity, I could understand such an attitude to some extent. However, historical data shows that this is absolutely not the case. Quite on the opposite, if we take into account the historic context, the mainland Chinese under the CPC have achieved an extraordinarily successful socio-economic development, whereas the record of Hong Kong in this field is quite lackluster.

This article is based on reliable data from international organizations and mainstream Western historians; nothing of it is based on official Chinese sources. After reading this article, you might be surprised that none of this data is ever mentioned in the Western media, and I can only say that I was at least as surprised as you when I found out about this. It looks as if mentioning the dark side of Hong Kong's past were a taboo in the Western media. The Chinese media don't make much effort either to explain the background of Hong Kong's development. It is definitely time that we start to hold the media accountable for providing balanced and comprehensive information about the topics which matter, instead of always taking sides with the rich and privileged.

However, this article is not the expression of any kind of hostility towards Hong Kong and its people. As an Austrian living in Switzerland, I will always criticize arrogant attitudes displayed by some Europeans against mainland Chinese or other ethnic groups even more sharply than similar attitudes displayed by Hong Kong residents. When I argue that Hong Kong has developed using a parasitic development model, we should not forget that the inventor of parasitic development through the tax haven model is Switzerland and that Austria has had a colonial empire, exploiting many neighboring people against their will. We must all strive to accept the dark sides of our own history.

World War 1 (1914-1918) was Europe's first industrialized large-scale war. It has traumatized the whole continent, but not enough to prevent World War 2… Source Deutsches Bundesarchiv on Wikimedia.

World War 1 (1914-1918) was Europe's first industrialized large-scale war. It has traumatized the whole continent, but not enough to prevent World War 2… Source Deutsches Bundesarchiv on Wikimedia.

In any discussion about history or development models, the most important is making a difference between on one side historic events and development models and on the other side individual people. If Hong Kong's wealth is due to a parasitic model of development, this does not mean that the Hongkongers are parasites. Even though Hong Kong's past development is based on exploitation of mainland China and on opium trade, Hongkongers are no thieves and drug dealers; many of them work hard and have got a hard time earning a living. Conversely, calling the mainland Chinese "locusts" or deriding them in insulting caricatures is unacceptable. The objective of the present article and the whole website is to work towards a better future: history must be analyzed based on solid data, undue privileges must be recognized and progressively reduced, so that we can achieve a better mutual understanding and a more equitable world. Another objective is of course to test the claim of Hongkongers that they can take criticism…

A brief historic overview is necessary to understand Hong Kong's development. Already before the First Opium War (1839-1842), China was quite well integrated into the world economy. Many Chinese products like porcelain, silk and tea were extremely popular with British consumers. For British traders, it was quite frustrating to see that the Chinese side of this trade was firmly in the hands of Chinese traders licensed by the Qing dynasty. An even bigger problem was that Great Britain had little to offer in return for Chinese products, except for opium which was produced in its Indian colony; however, trading opium was illegal in China.

Many Chinese products like silk, tea and porcelain were very popular among the British aristocracy. Alan Maley, "A Private Conversation", Source: Svistanet.

When in 1839, in a push to curb opium smuggling, the Chinese government seized and burned a shipload of opium from a British trader, the British navy shelled, looted and burned Chinese coastal cities, forcing the Chinese government to sign a treaty which opened China to British traders and ceded Hong Kong to Great Britain. Opium trade remained illegal, but smuggling increased massively. After a second Opium War (1856-1860), Great Britain even forced China to legalize opium trade, which led to further increase in this deadly activity.

Opium den in Shanghai. Photo from Samuel Merwin, Drugging a Nation: The Story of China and the Opium Curse, 1908.

After 1839, much of the British trade with China, including most of the opium trade, transited through Hong Kong. When you know that at the height of the opium trade in the 1880s, more than 4000 tons of opium were sold by Great Britain to China each year, you might get an idea of the "gift" which the British navy had given to Honk Kong… and to the Chinese society on the mainland. The term "parasitic development" is more than appropriate to describe this model. Despite this, Hong Kong's socio-economic development is not really impressive, be it during that period or in more recent times.

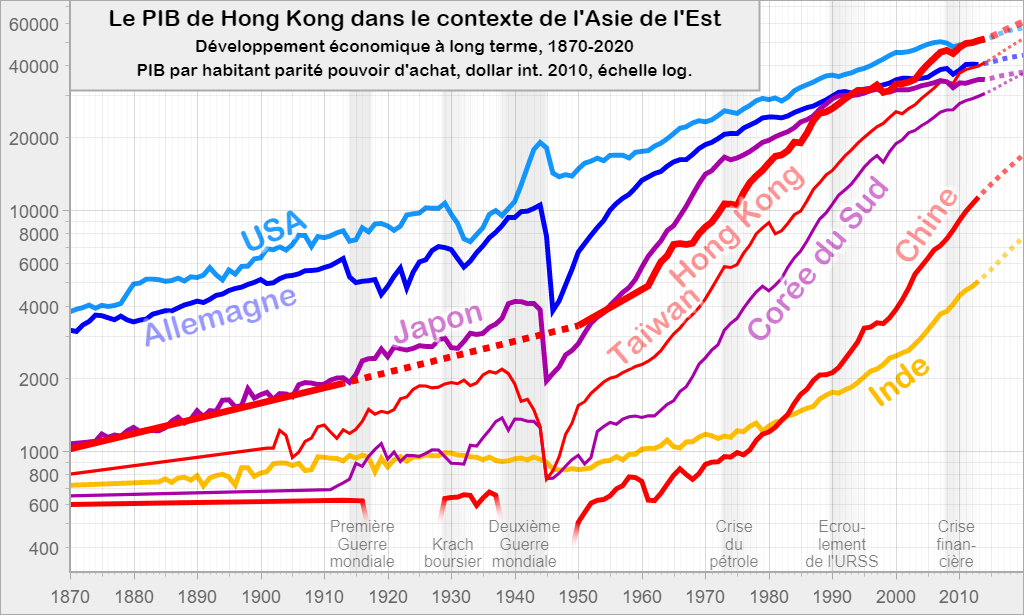

The chart below represents GDP per capita PPP (purchase power parity) on a logarithmic scale for a couple of Asian and Western countries and regions; this indicator is considered to be the best way of measuring the standard of living.

The fat red line represents Hong Kong. Before 1950, only a few estimates are available; between 1913 and 1950, we don't even have rough estimates. However, the data we have got gives us a fair idea of Hong Kong's development and allows a comparison with other countries in the region.

If we compare Hong Kong's economic development to Japan's, the curves might look quite similar, but the underlying conditions were not. The Japanese government had to improve the living conditions of the whole population of the country, including many remote rural areas in mountainous regions. Hong Kong, on the other hand, only had to develop a port city which could let in or send back to mainland China exactly the number of workers which were needed by the economy. Hong Kong never assumed any responsibility for the huge majority of the population which produced the goods they traded. Japan, on the other hand, has achieved fast socio-economic development not only on its whole territory; in its colonies South Korea (1910-1945) and Taiwan (1895-1945), it has achieved much faster development than what the local elite achieved before the Japanese colonization.

It goes without saying that the militaristic model chosen by Japan must be considered as totally unacceptable and it is our duty to do everything we can in order to make sure that nobody tries to use this model in the future. However, it allows us to evaluate what kind of development was possible under a highly organized and motivated traditional elite (i.e. motivated by military conquest).

Right from the start in the 1850s, Japan's development was strongly influenced by a militarist ideology. Source: Wikimedia.

After the Second World War, the development of both Japan and Hong Kong accelerated. During most of Mao's era, US sanctions against China were a serious obstacle to free trade; Hong Kong's activity in trade with mainland China was strongly reduced. However, this had no impact on Hong Kong's development. The chart above shows that Hong Kong's growth picked up speed around 1960; even during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), growth did not slow down. When the sanctions were lifted and Deng opened up China to the world, growth in Hong Kong did not accelerate either. During the Mao era, the loss from the reduction of trading was in part compensated by the buildup of an industrial production basis in Hong Kong itself. On the other hand, the sanctions against mainland China quickly became a new source of income for Hong Kong. Sanctions are known to be a disaster for the targeted country and to be at the same time a blessing for neighboring trading countries which will hugely benefit from bypassing the sanctions. They pretend to buy goods for their own consumption or industrialization, then they sell them with a huge benefit to the country targeted by the sanctions which desperately needs them. Creative minds will always find new ways of parasitic development…

Despite Hong Kong's privileged location and various sources of easy income, none of which Japan could enjoy, Japan has done as well or better than Hong Kong in overall development. Growth was roughly similar between 1870 and 1950, as far as the little data available for Hong Kong can tell us. After 1950, with a similar starting point, Japan has developed significantly faster. It took Japan until 1973 to reach the level of the UK (1955-1973: 8.2% per capita GDP growth per year), whereas Hong Kong needed until 1988 to achieve this (1960-1988: 6.2% per year). From roughly the year 2000 on, Hong Kong overtook Japan; it has by now even overtaken the USA. We will see from many examples that this is generally a sign of a parasitic model of development: only countries and regions using the tax haven or port city model of development (or both) achieve such high standards of living ?L?. In recent decades, Hong Kong has used its experience with international trade and finance in order to become one of the most important tax havens in the world. Concretely, this means helping the richest people from other countries to hide their wealth in well-protected bank accounts, leaving it up to less wealthy people to pay the taxes necessary for the government to provide basic services. This is definitely just another tool of parasitic development.

The example of mainland China under the Communist Party ?L? shows us what a ruling elite which is committed to social development can achieve under incomparably more difficult conditions. It took Honk Kong more than one hundred years of relatively slow growth (1842-1960) before it could achieve a period of fast growth: 28 years (1960-1988) at 6.2% per year. In Japan, the period of slow growth lasted roughly 90 years (1860s-1955). In comparison, it took China 27 years (1949-1976) after the first signs of socio-economic development appear on nation-wide statistics before it could achieve more than 35 years of fast growth: 1976-2013 at 6.9% per year. The following table sums up the economic development for Hong Kong, Japan, China and India; it shows the average yearly growth rates of the first phase (slow growth) and second phase (fast growth):

| Per capita purchase power parity GDP growth rates for several Asian countries and regions | |||||

| Phase 1 (slow growth) | Phase 2 (fast growth) | ||||

| Country / region | Duration | Data availability |

Growth rate |

Duration | Growth rate |

| Hong Kong | 1842- 1960 | 1870- 1960 | 1.7% | 1960- 1988 | 6.2% |

| Japan | 1860s- 1955 | 1870- 1955 | 1.6% | 1955- 1973 | 8.2% |

| China mld. | 1949- 1976 | 1950- 1976 | 2.5% | 1976- 2013+ | 6.9% |

| India | 1947- 1990 | 1947- 1990 | 1.8% | 1990- 2013+ | 4.6% |

It is quite obvious that Hong Kong's economic development is not bad, but not exceptional either.

Development in cities is not only illustrated by spectacular skylines, but also by quiet and clean suburbs like here in Beijing. Photo Otto Kolbl, 2013.

With regards to China, we must also consider the conditions before the Communist Party came to power. In 1949, Mao Zedong took over a country which had previously gone through a period of warlordism and total breakdown of state institutions (1916-1928) and where huge territories were still in the hands of warlords. What is more, he has been able to bring impressive economic development to a vast country which is naturally handicapped as compared to most other Asian countries by the fact that many of its densely populated areas are thousands of kilometers away from the sea. If we take into consideration all these factors, Hong Kong's development blatantly shows the failure of the British colonial model.

The comparison with Japan and mainland China might give us some clues as to why they did so much better than Hong Kong: Japan and China both emphasized social development, even if they did so for different reasons. Of course, social development will not be achieved by good intentions alone, it requires massive long-term investments in at least three fields where the role of the state is essential: infrastructure, education and healthcare. The British colonial administration had neither the good intentions nor the will to provide the necessary funding for a decent social development.

In the case of Hong Kong, infrastructure was secondary: the main transport infrastructure which was vital in its development was the port, a gift from Mother Nature (arguably robbed by the British navy). All other vital infrastructure is much cheaper to build for a city with its high population density than for a whole country where roads etc. have to be built not only within the cities, but also between cities and in the countryside.

In remote areas, like here in the Tibetan areas in Sichuan province, building the life-sustaining infrastructure is much more expensive than in densely populated cities. Photo: Dream Tirong, a Tibetan monk.

On the other hand, universal high-level education is even more important in a trade-based economy like Hong Kong than in countries which have chosen a development model mainly based on industrialization like China and Japan. Similarly, a good healthcare system is vital in a port city with a high population density where epidemic illnesses from all across the world can easily be brought in by each ship docking in the port. The British colonial administration of Hong Kong was obviously not really aware of the importance of social development: according to Western historians, the Japanese occupiers (1941-1945) did more to develop basic education and healthcare services for the whole population than the British, who cared mainly about the well-being of the white population and left the Chinese to fend for themselves.

Opium has certainly also played a role in slowing down economic growth in Hong Kong before World War II. On the other hand, opium addiction was certainly less destructive in Hong Kong than in mainland China, where it was extremely widespread among the ruling elite; this lead to the breakdown of the whole structure of the society. In Hong Kong, addiction was quite rare among the white colonial rulers, but widespread among the lower social classes. It helped unqualified "coolie" dock workers to endure their pain and suffering and has certainly contributed to protect the British from any serious and organized challenge to their rule.

This sculpture in Singapore reminds us that the wealth of the region (and of the whole world) has been built by workers living in misery. Some liberal-minded Hong Kong residents have got a tendency to forget this. Photo William Cho.

All this can explain quite well why during the colonial period, Hong Kong developed relatively slowly in comparison with China and Japan, even though Hong Kong was a particularly privileged city: it is quite well-known that apartheid regimes tend to perform poorly in development. Such regimes rely on the exploitation of a miserable majority by a tiny privileged elite; the elite will do little to improve the living conditions of the poor. Since indicators of social development show the average over the whole population, such regimes do not get good results.

On the other hand, it is quite obvious that in the last few decades, Hong Kong has reached a very high level of development. So, has the recipe of the British colonial masters finally worked after their departure? Not really. Obviously, indicators of socio-economic development are very positive, but this is simply due to the fact that those who have now become the privileged elite (the Hongkongers) are physically separated from the manual laborers who make their lifestyle possible (the factory workers in mainland China). It is understandable that the Hong Kong residents want to keep it like this and to prevent mainlanders from moving to the island. However, I would like to draw their attention to what the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says about this:

Article 13

(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

Well yes, settling in Hong Kong is part of the human rights of each mainland Chinese…